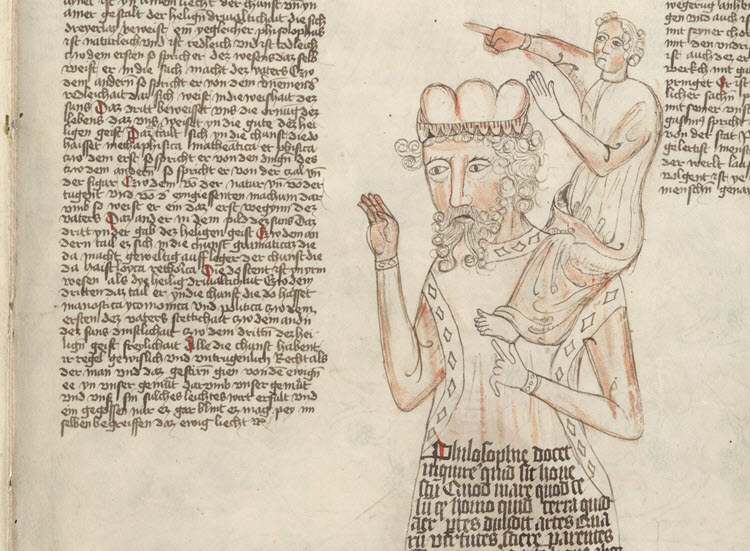

Standing on the shoulders of giants

Reach great heights by building upon the achievements of others

Image: Library of Congress

As a student, you may often feel daunted by your professors. During my college years, I remember that I often felt intimidated by the depth and breadth of information and theories my literature professors were able to cite ad hoc during their lectures. How did they know all of that? And could I ever be that knowledgeable or insightful, too? It seemed unlikely at the time.

When you feel this way, it’s helpful to know that many of the most brilliant minds in your field have experienced this same type of imposter syndrome. Like you, they started out by looking up to the giants in their field. Despite feeling inadequate, they persevered and eventually carved out their own space in academia because they were able to build upon the work of their mentors.

This ability to use the work or findings of others to make your own contributions to knowledge is what’s behind the concept of “standing on the shoulders of giants”. Its most well-known formulation comes from a letter Isaac Newton wrote to one of his peers in 1675 regarding the discoveries about color that he had recently published. He writes, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants”.*

It’s a humble acknowledgement of the importance of the discoverers who came before him. By building upon their findings he was able to make a scientific breakthrough, even if he only considered himself to be a mere dwarf.

The idea of dwarfs standing on giants is one that goes back to at least the twelfth century (Merton 1993). So why do we now most often associate the phrase with Newton? One reason might be that in the next century, it would come to reflect the Zeitgeist of the time.

The 100 years after Newton penned these words would see the development of a system that would shape academic writing through the present day: the footnote citation system. Prior to that century, authors previously had used marginal notes and glosses for additional commentary (Conners 1998). Attribution beyond the author’s name was seldom needed since it was assumed that readers would be familiar with the same set of classical or religious texts. In addition, citing a page number before the invention of the printing press simply didn’t make sense; when books were copied by hand, each book would have its own individual pagination.

With the development of the printing press, page numbering became fixed (Conners 1998, p. 8). This meant that authors could point directly to where they found an idea or quotation. The number of books available also increased rapidly. In addition, there was a cultural shift in Europe and Great Britain where it became increasingly expected that authors would cite their sources. By the end of the 18th century footnotes became established as the method of choice for doing this, presumably because they took up less space and were less distracting than marginal notes (Connors 1998). Footnote citations were a way for authors to give credit to the giants that had come before them and they allowed readers the ability to find and read the source themselves – both of which are some of the same reasons we cite our sources today.

So, the very ordinary and sometimes dull process of creating citations has at its root a very lofty thought indeed: we acknowledge the giants who went before us, and we advance their findings as we can, even if it’s just in small ways.

But does the metaphor still work today? During the Enlightenment the number of classical authors or contemporaries one might cite was smaller in number. Many of these thinkers and discoverers worked in what today would be several academic disciplines. By being the first to make many large discoveries, they could truly be thought of as giants.

However, in the 21st century, academic disciplines are typically more crowded. While you may be familiar with some of the big names in your field, you likely won’t be familiar with all of the authors you cite for a paper, journal article, or thesis. Instead of there just being a few big names dominating each field, knowledge is pushed forward bit-by-bit through the efforts of many individual scholars.

This is a point made by the PhD student and blogger Tom Donoghue in a post entitled “I don’t stand on the shoulders of giants”. He contends that a new metaphor is needed. Instead of just standing on the shoulders of a few individual people, he suggests the idea of crowd surfing. As he writes “If ever there was truly a time in which individuals independently pushed science forwards, it is not today. Modern science is a team sport, and the words we use should reflect that, and give credit to the immense number of people contributing to its developments” (Donoghue 2017).

So, if the authors we cite these days are more like a crowd, how do you keep track of them? Remembering which idea came from which author is no longer an option, not to even mention the details of the work and the page number. Reference management software can help since it aids you in managing your sources, keeping notes on them, and easily finding them again.

Even if we no longer stand (only) on the shoulders of giants, one thing hasn’t changed: we stand on the shoulders of the researchers who have gone before us or who are our peers. And to give them the credit they deserve, we still cite them and their work, even if we now also use other forms of citation besides footnotes to do so.

This use of others’ findings is an essential element of knowledge production. So, the next time you feel daunted by the scholars you look up to, take comfort in the fact that someday, like Isaac Newton, you too may be able to build upon their achievements to make your own contribution to knowledge.

What do you think about the metaphor “standing on the shoulders of giants”? Do you agree that the image of “crowd surfing” fits better today? We’d love to hear your thoughts on our Facebook page!

*Spelling and wording modernized

References

Blyth, C. (2018, June 21). Hard to believe, but we belong here: Scholars reflect on impostor syndrome. Times Higher Education (THE). Retrieved from https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/hard-to-believe-but-we-belong-here-scholars-reflect-on-impostor-syndrome

Connors, R. J. (1998). The rhetoric of citation systems, Part I: The development of annotation structures from the renaissance to 1900. Rhetoric Review, 17(1), 6–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350199809359230

Connors, R. J. (1999). The rhetoric of citation systems, Part II: Competing epistemic values in citation. Rhetoric Review, 17(2), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350199909359242

Donghue, T. (2017, May 24). I Don't Stand on the Shoulders of Giants. Blog post. Retrieved from https://tomdonoghue.github.io/sc/2017/05/24/IDontStandOnTheShouldersOfGiants.html

Merton, R. K. (1993). On the shoulders of giants: A Shandean postscript. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Newton, I. (1675, February 5). Isaac Newton letter to Robert Hooke, 1675, Historical Society of Pennsylvania Simon Gratz autograph collection (#0250A), Box 12/11, Folder 37.